MESA COUNTY, Colo. (KDVR) — On the edge of a corral on the Western Slope, dozens of cows and calves are kicking up blowing dust across a dry and barren field.

“Our life is cows and more cows,” said cattlewoman Janie VanWinkle. “We like to say we care for the land, the livestock and our community. Everything we do is focused there.”

The VanWinkles, a long-time family of ranchers, are separating and vaccinating calves born in May and June.

“Get back T-Bone,” the cattlewoman called to their herding dog as she grabbed the back of a calf’s leg.

On a cloudless, hot afternoon in June, the couple caught calves, which weigh about 150 pounds each, and vaccinated them for respiratory disease.

“We catch a calf and lay him down to get vaccinated,” said VanWinkle. “We tag them with the same number of the mom.”

Ranchers like the VanWinkles are adapting to what scientists are calling a megadrought across Colorado’s Western Slope.

“We were managing about 550 head of cattle and we are down under 500 cows at this point and time,” said VanWinkle, a fourth-generation cattlewoman who oversees the herd with her husband, Howard, and adult son’s family.

“We use less of the resources because there is less resource there,” said VanWinkle. “The drought is right here in our face. It is absolutely first and foremost in all of our thoughts.”

The intense afternoon sun is motivation for the couple in their 60s as they move the calves and mother cows to the higher elevations of the Grand Mesa for the rest of the summer.

“That’s a way of managing the resources. In the summer we go to the higher elevations,” said VanWinkle. “We let the properties here in the valley and the lower elevations recover through the summer, then we will come back to them in the fall or winter.”

Ranchers said it has been so dry, they are moving cattle more often to find suitable vegetation.

“We are in four years out of the last five being seriously dry, and the accumulative effect is certainly starting to take its toll on the landscape,” VanWinkle said.

The ranching family leases and owns several properties across Mesa County, but they have also taken a cut on that part of their operation trimming cows grazing in the National Forest on the Uncompahgre Plateau.

“We have taken a 20% cut on that, meaning we are taking 20% less cows there over the last two years,” said VanWinkle.

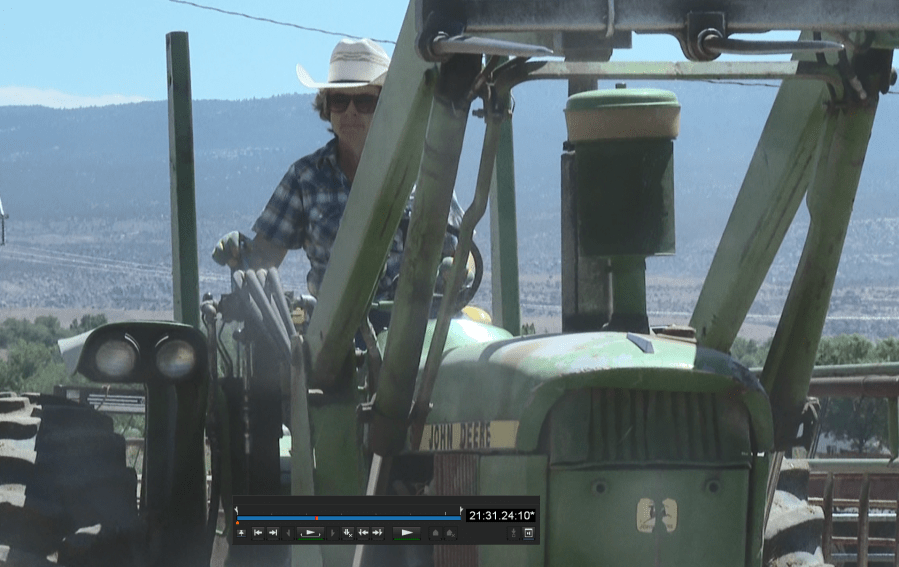

Besides moving cattle, ranchers are also depending more on hay. The chugging and clinking start of a tractor caught the attention of dozens of cows in a field near Grand Junction as the cattlewoman maneuvered the tractor’s fork to pick up a 1,400-pound bale of hay. It’s enough to feed about 40 cows for one day.

“From an environmental standpoint, normally these cows would not still be eating hay. They would be somewhere out on pasture, but because of the ongoing drought, we are feeding hay,” said VanWinkle. “And hay is anywhere from $250 to $300 a ton.”

The ranchers are also farmers putting up 600 tons of hay each year to ensure feed through the winter months.

Fewer heads of cattle mean less income for the herding family.

“We still have to keep the lights on, we will have fuel, we still have to fertilize the field. That overhead gets spread out over a few cows,” said VanWinkle, whose contemplating the future of their farm.

Fewer cattle also add up not only for the rancher but for Mesa County’s economy with each head of cattle contributing $600 to the local economy.

The ongoing drought leaves Grand Valley’s cattle families thinking about their acreage and the times ahead.

“If we don’t take care of the grass, if we don’t care for those water resources, then they won’t be here 10 years from now,” said VanWinkle. “The drought makes us think, what does that future look like?”

State-wide cattle and calves are Colorado’s number one agricultural commodity with 2.8 million head of cattle in the state.

Check out the VanWinkle Ranch Facebook page for more information.

For more coverage of this story, visit our Colorado River Crisis coverage page.