PALISADE, Colo. (KDVR) — Known for its incredible beauty as it carves through Colorado’s central mountains, the Colorado River and its tributaries are a crucial water source vital to 40 million people.

“I would say there is not a single resource that is more important than the Colorado River in our state,” Andy Mueller, general manager of the Colorado River District, said. “Every sector of our economy depends on having an adequate water supply.”

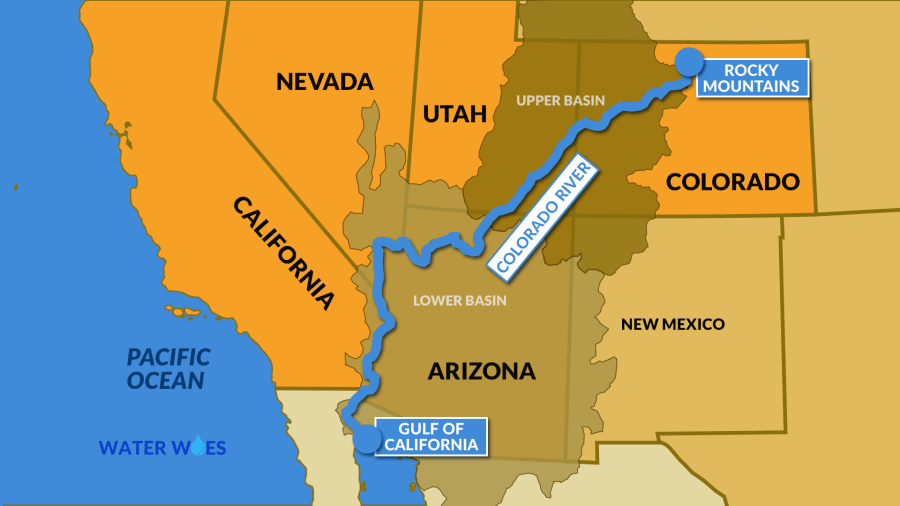

Starting in Rocky Mountain National Park at 10,184 feet, the river grows from a trickle of a trout stream into a necessary waterway running through the West. The Colorado River is the sixth largest river in the U.S., and flows 1,450 miles with its basin reaching seven states including Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona and California where it empties into the Gulf of California at sea level in Mexico.

But year after year, the powerhouse of a river is less powerful producing less water and threatening to forever change the lives and businesses who rely on its touch.

Fishing in the Colorado River Basin

“We embrace it. We protect it. We support it and we live in it,” Pete Mott, who has called the river his office for 31 years, said. “It’s everything.”

Mott’s commercial fishing business, Trout Trickers, has one goal in mind for tourists: catch trout.

Temperatures rose quickly on the Eagle River in June where Mott guided three boats of anglers on a full day of fly fishing.

“I will actually carry a thermometer and we will be measuring temperatures and making a decision that favors the fish and stopping our angling, not catching them when they are already experiencing tough conditions,” Mott said.

Tough conditions start when the water warms over 68 degrees and the fish quit biting. Some rivers in the state have warmed to the point that Colorado Parks and Wildlife have asked people to stop fishing at noon.

The river’s impact on farms and tourism

From anglers to farmers and ranchers, the river supports businesses hydrating 5 million acres of agricultural land and supplying 173,000 farming jobs.

“We are all in the same boat,” Rainer Thoma, the winemaker and manager for Grande River Vineyards, said. “We just got to work together, all the farmers.”

Tourism accounts for more than $30 billion in Colorado’s economy supporting Palisade’s growing wine-making industry. Grande River Vineyard’s Hotel and Wine Country Inn are surrounded by rows of grapevines giving tourists a close-up look at their vines.

“Tourism is our main source of revenue. So, tourism is just key to the success of the winery and the hotel,” Thoma said.

Overall, irrigated agriculture contributes $47 billion to the state’s economy.

Down the road at Sauvage Spectrum Estate Winery and Vineyard, the owners have changed the way they irrigate using a micro-sprinkler system that pulls less water.

“By doing that, it makes us probably 98% efficient,” owner Kaibab Sauvage said. “When we first started, we flood irrigated the vineyards because that is traditionally how irrigation was done on peaches over the years.”

How the drought impacts more than plants

The river is in crisis with a rise in temperatures decreasing flow by 20% over the last 20 years. The dry and warm combination is forcing constant changes for ranchers.

“Normally, these cows would not still be eating hay. They would be somewhere out on pasture, but because of the ongoing drought we are feeding hay and that hay is anywhere from $250 to $300 a ton,” Janie VanWinkle, a Mesa County cattlewoman, said. “The drought exacerbates everything we do.”

Ranchers like the VanWinkles are relying on hay longer as the countryside vegetation dries up. They are also moving cattle more often to find suitable grazing land.

“We want to feed people. That’s what we do and why we do it,” VanWinkle said. “Some of the water rights in the Grand Valley are some of the oldest water rights, but if there is no water there, it doesn’t matter what your right is.”

Colorado’s Grand Valley landscape is as dry as the ranchers have seen it.

“The drought is right here in our face. It is absolutely first and foremost in all of our thoughts, everything we do,” VanWinkle said. “The drought makes us think, ‘What does that future look like?'”

VanWinkle is a fourth-generation Colorado rancher who has raised cattle her entire life.

“Everything is about the land, the livestock or this community that we call home,” she said.

The impact can be seen in the livestock she cares for.

“We were managing about 550 head of cattle and we are down under 500 cows at this point and time,” VanWinkle said. “We still have to be sustainable. We will have to make a living. We still have to be able to afford to do this, if you will, so when those numbers go down the overhead does not.”

Laws and water rights on the Colorado River

Ranchers and farmers rely on the Colorado River, which was essentially over-promised 100 years ago during the first river rights agreement.

“The problem is a simple math problem at the time. They were in a very wet period in the early 1920s. They assumed a lot more water was in the river on a regular basis than actually was so they divided up more water than there was,” the Colorado River District’s Mueller said.

The Colorado River Woes story continues on FOX31 News Thursday night. We’ve included a full schedule at the bottom of this article.

In 1922, the Colorado River Compact designated upper and lower basins dividing the river between the upper states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico, and the lower states of California, Arizona and Nevada.

While the same compact exists, numerous court decisions, contracts and projects collectively regulate the river’s water.

“What has happened in the last 22 years, the supply has diminished because it’s so hot and dry. And, at the same time, the demands in the lower basin have continued to be greatly in excess of what they are entitled to,” Mueller said.

One of Mueller’s fears, he said, is that the trends will continue and the impacts could be severe. So severe that water districts like Denver Water, which supplies water to 1.5 million people, are planning for the future.

“That supply is critical to the city and to its residents,” Todd Hartman with Denver Water said.

The water district pulls half of its water from the Colorado River moving it through an elaborate system of tunnels, pipes and reservoirs.

“That’s critical water for us because that is snow that builds up over the four, five, six winter months and we can rely on all year long,” Hartman said.

Denver Water’s reservoirs will only reach 92% of capacity this year, and while drought is a major factor so is the southwest’s overuse of water.

“There’s no question that there is a crisis on the Colorado River,” Hartman said.

Where the river goes after Colorado

The river leaves Colorado flowing southwest through Utah to the country’s second-largest reservoir, Lake Powell, which continues to recede despite efforts to keep hydropower turning for 3 million customers.

Nearly 2,000 miles of sandstone red canyons bleached white over the years leave a “bathtub ring” around the lake. It’s a glaring reminder of how low the water is at this popular recreation spot.

Lake Powell has had to close many areas due to low water levels (Credit: KDVR)

Lake Powell view from Alstrom point in Glen Canyon National Recreation area.

A Utah State University research team pulls in a gillnet net at Lake Powell on Tuesday, June 7, 2022, in Page, Ariz. They are on a mission to save the humpback chub, an ancient fish under assault from nonnative predators in the Colorado River. (AP Photo/Brittany Peterson)

FILE – A boat cruises along Lake Powell near Page, Ariz., on July 31, 2021. Federal water officials have announced that they will keep hundreds of billions of gallons of Colorado River water inside Lake Powell instead of letting it flow downstream to southwestern states and Mexico. U.S. Assistant Secretary of Water and Science Tanya Trujillo said Tuesday, May 3, 2022, that the move would allow the Glen Canyon Dam to continue producing hydropower while officials strategize how to operate the dam with a lower water elevation. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File)

This Aug. 21, 2019 image shows Lake Powell near Page, Arizona. A plan by Utah could open the door to the state pursuing an expensive pipeline that critics say could further deplete the lake, which is a key indicator of the Colorado River’s health. (AP Photo/Susan Montoya Bryan)

Bill Schneider stands near Antelope Point’s public launch ramp off Lake Powell, which closed to houseboats as early as October of 2020 Saturday, July 31, 2021, near Page, Arizona. This summer, the water levels hit a historic low amid a climate change-fueled megadrought engulfing the U.S. West. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

FILE – In this July 20, 2014 file photo, a bathtub ring of light minerals shows the high water line near Hoover Dam on Lake Mead at the Lake Mead National Recreation Area in Nevada. Six states in the U.S. West that rely on the Colorado River to sustain cities and farms rebuked a plan to build an underground pipeline that would transport billions of gallons of water through the desert to southwest Utah. In a joint letter Tuesday, Sept. 8, 2020, water officials from Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Wyoming urged the U.S. government to halt the approval process for the project, which would bring water 140 miles (225 km) from Lake Powell in northern Arizona to the growing area surrounding St. George, Utah. (AP Photo/John Locher,File)

“We literally have about 33% of the total system storage,” Mueller said. “I don’t know how you feel, but having a savings account that’s only 33% full makes me very concerned.”

Due to the ongoing drought across the West combined with the lower basin’s overuse of water, the Bureau of Reclamation gave the seven states until mid-August to come up with a plan to cut water use so large reservoirs like Lake Powell could be kept at levels that allow hydropower production continues.

The U.S. Department of Interior announced action last week and released the Colorado River Basin August 2022 24-Month Study, which guides the future operations of Lakes Powell and Mead.

“The Colorado River Basin is facing unprecedented challenges, and the 40 million people who rely on this critical resource are depending on the basin states and federal government to develop inclusive, sustainable solutions that protect the system and its infrastructure now and into the future,” Colorado River Commissioner Becky Mitchell said. “I am proud to say that the upper division states are meeting the moment with our 5 Point Plan, and our focus now turns to implementation, including additional conservation efforts to maximize efficiency in all sectors.“

Mitchell also said the upper basin plan relies on the lower basin states taking action.

In the spring of 2022, the Bureau of Reclamation took drought response action to keep Lake Powell turning power through April 2023. The plan allowed the release of an extra 500,000 acre-feet of water upstream from Utah’s Flaming Gorge Reservoir. The government also reduced the annual release volume from the reservoir from 7.48 million acre-feet to 7.0 million acre-feet. Still, lake levels are expected to drop through 2023.

“We are predicted to have 55% of the runoff into Lake Powell this year,” Mueller said. “We should expect a drop in Lake Powell over this water use season to be as much as 25 to 30 feet of elevation.”

Water levels in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are the lowest since the reservoirs along the river were first filled.

Planning for Colorado River water in 2023 and beyond

In July of 2022, the Colorado Water Conservation Board released a draft update of the state’s water plan which includes tools to mitigate the impacts of drought, aridification and climate change.

The plan does not include any mandatory water cuts for Colorado and instead argues that because the lower river basin states use twice as much water, the cuts should happen downstream.

“If the federal government is going to look for water savings and water conservation plans, we’ve given. That’s what we would say. We’ve given at the office. We would like to see the lower basin step up and do what we have done. We all need to live in this new reality that we have,” Mueller said.

According to the conservation board, the upper basin used 3.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water in 2021, which represents a 25% reduction from 2020’s 4.5 million acre-feet of water.

To help fund change, the Federal Infrastructure Bill provides upper basin states with $50 million for drought contingency plan implementation. Colorado’s 2023 Water Plan draft is currently out for public review until Sept. 30.

Colorado and the Upper River Commission are also preparing for water negotiations that will extend beyond 2026. The negotiated agreements will replace the current 2007 guidelines which expire at the end of 2025. Those negotiations are expected to begin later in 2022 or next year.

“If we don’t take care of the grass, if we don’t care for those water resources, then they won’t be here 10 years from now,” VanWinkle, the cattle rancher, said.

Meanwhile, the report predicts the state could warm another 2.5 degrees by the middle of the century which would mean even more changes are necessary.

“We have built up a system that has worked very well for the last 100 years, it is now in crisis. Water is life, so what we need to do is adjust our lifestyles to live within our water budget,” Mueller said.

You can watch the following stories related to the Colorado River Crisis on FOX31 News:

- Drought and other climate impacts on Colorado River fishing

- Western Slope wine may be trending now, but its future is in jeopardy

- Cattle and the Colorado River – life in the balance (Thursday, 9 p.m.)

- What does the Colorado River drought mean for Denver and the front range? (Thursday, 10 p.m.)

As you can see outlined above, the Colorado River crisis’ impact goes beyond rafting and recreation. We’ll have continuing coverage of this story on KDVR.com and FOX31 News.