DENVER (KDVR) — It’s been described as “the only acceptable goal” for the Mile High City when it comes to traffic deaths, albeit a lofty one. Vision Zero was announced in 2016 with the goal to bring road deaths and serious crashes down to zero by 2030.

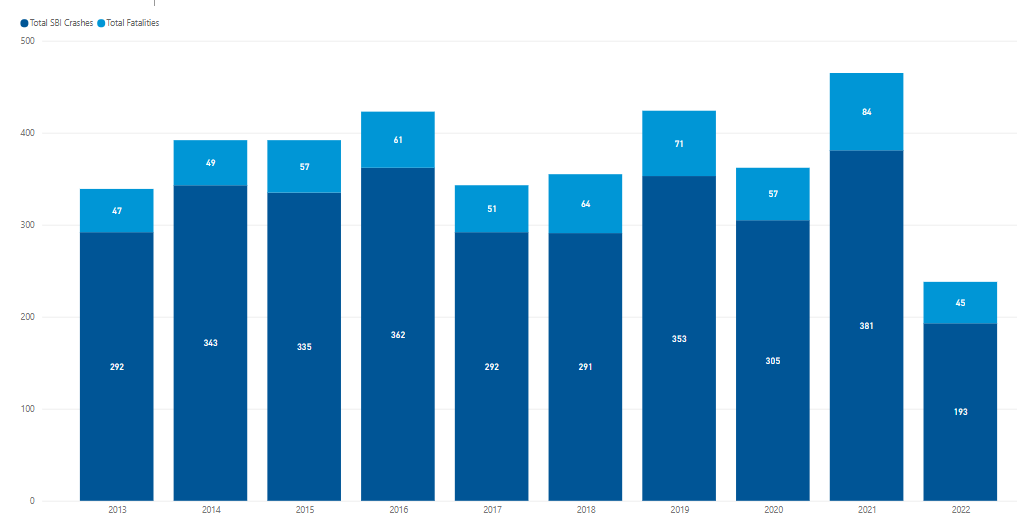

But the data shows Denver is trending in the wrong direction, despite nearly completing a five-year action plan for Vision Zero. The city saw a record-high year for traffic deaths in 2021 compared to the last two decades, and trends show that 2022 may be even worse for serious road crashes and deaths in Denver.

“We know people are going to make mistakes and errors when they’re traveling, when they’re driving,” said Denver Department of Transportation and Infrastructure spokeswoman Nancy Kuhn. “How do we minimize the damage that can occur as a result? How do we make our streets safer?”

According to the Vision Zero 2021 Report, reckless, careless and aggressive driving, speeding, DUI and failure to wear seatbelts were the most common factors in fatal crashes, along with failing to wear helmets for motorcyclists.

Some methods are subtle and others stand out. DOTI has been systematically reducing the speed limit on certain stretches of what’s called “high injury networks” which are mainly made up of major city arterial roads like Colfax Avenue and Colorado Boulevard. The department recently reduced the speed limit to 25 miles per hour from 30 on a stretch of Santa Fe Boulevard.

According to DOTI, 5% of Denver’s roads account for 50% of traffic fatalities. But slowing people down isn’t all about just reducing speed limits.

How the city is handling Denver drivers

“What are some of the treatments we can put on our streets to slow people down?” Kuhn said. “Because we know if we slow people in cars down we can improve the outcomes if someone should get in a crash.”

DOTI is doing this through road redesigns, more signage, designated protected bike lanes, automated speed enforcement, better lighting at intersections, eliminating some left-hand turns to prevent t-bone accidents and more. The department is also creating more posts and paint along major roads in the median to try and reduce the total distance pedestrians need to cross.

“These are the type of treatments that we’re doing, we know that they work and we are accelerating our efforts,” Kuhn said. “We know we have more work to do.”

But despite all these efforts, road deaths are still getting worse since 2016. There have been 45 road deaths in Denver as of July 20, 15 of them pedestrians. Kuhn pointed to the trends in the data and how COVID’s community impact has lessened over the past two years, so the behavior is returning to normal.

“It looks very similar to 2019 so pre-COVID levels,” Kuhn said. “So what we may be seeing this year is people coming out, they’re driving more, they’re walking more, they’re coming out of that stay at home. So we’re gonna see more activity on our streets so that means more potential for conflict when they’re walking and driving so we’re going to need to continue our work to make our streets safer for people.”

DOTI has a rapid response team that is deployed when pedestrians are killed in crashes, like a recent hit-and-run at Colfax and Quebec. The team will work with police on what happened in the crash.

“Is there something we can do now, quickly to minimize the chance of that happening again?” Kuhn said. Those targeted responses for road safety are paired with the planned improvements.

What Denver is doing to increase cyclists’ safety

Bike lanes will continue to be built out by the city, and Kuhn mentioned feedback from bicycle advocates saying the work so far is good, but there needs to be a stronger network and more protective infrastructure for cyclists.

The sentiment is echoed by Piep van Hueven, the director of government relations for Bicycle Colorado, who said it’s important that Denver has a Vision Zero program, but the program has delivered a mixed bag of results.

“On the one hand it’s clear that Denver’s invested in some more bike lanes, some better pedestrian crossings and visible temporary treatments with on-street paint and bollards that help increase street safety,” van Hueven said. “On the other, many street improvements are still low-quality or temporary design. We could do so much better – using concrete design instead of plastic bollards, or creative elements like planters and art that make the city streets both more protected and more enjoyable.”

What’s being done to free up road space?

Executive Director of the Denver Streets Partnership Jill Locantore told FOX31 that the missing link in Denver’s Vision Zero plan is the bus. Her belief is transforming those high injury network roads to prioritize bus transit will incentivize other modes of transportation and safety, as outlined in the organization’s 2022 Vision Zero Call to Action.

“When we redesign streets to prioritize the bus, we can still move lots of people quickly over long distances, but much more safely and without taking up nearly as much street space,” Locantore said during the organization’s Ride and Walk of Silence. “When we free up street space from cars, we can add better sidewalks, and bike lanes, and safer crossings, and trees that provide beauty and shade. When we leave the driving up to trained professionals, we can relax and enjoy the ride, without worrying that in a moment of distraction, we might kill an innocent person.”

Kuhn said even though the data doesn’t reflect positive momentum for Vision Zero, she said it has changed the approach and the culture of DOTI.

“I do not believe it’s been a failure,” Kuhn said. “The commitment alone has changed us as a city and as a department. It puts safety at the forefront of what we do.”