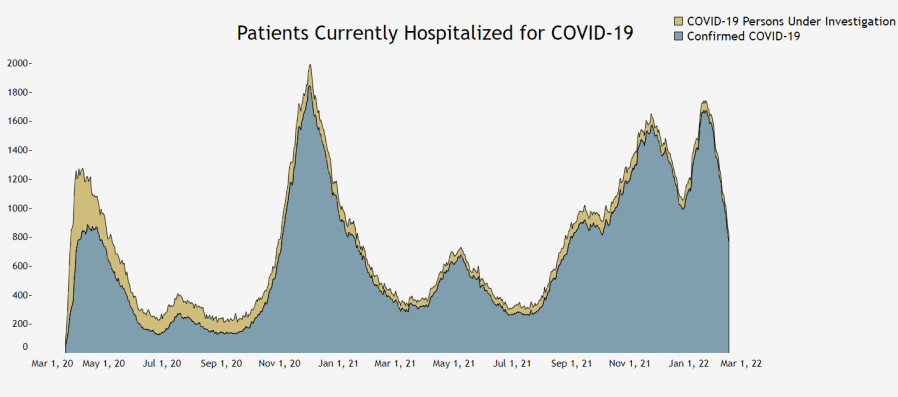

DENVER (KDVR) — The state hasn’t seen COVID-19 hospital levels this low since early October, and yet Colorado hospitals are still juggling a capacity crunch in the intensive care unit and for acute care beds.

So why are hospitals still struggling to keep up with COVID cases down? There’s no simple answer.

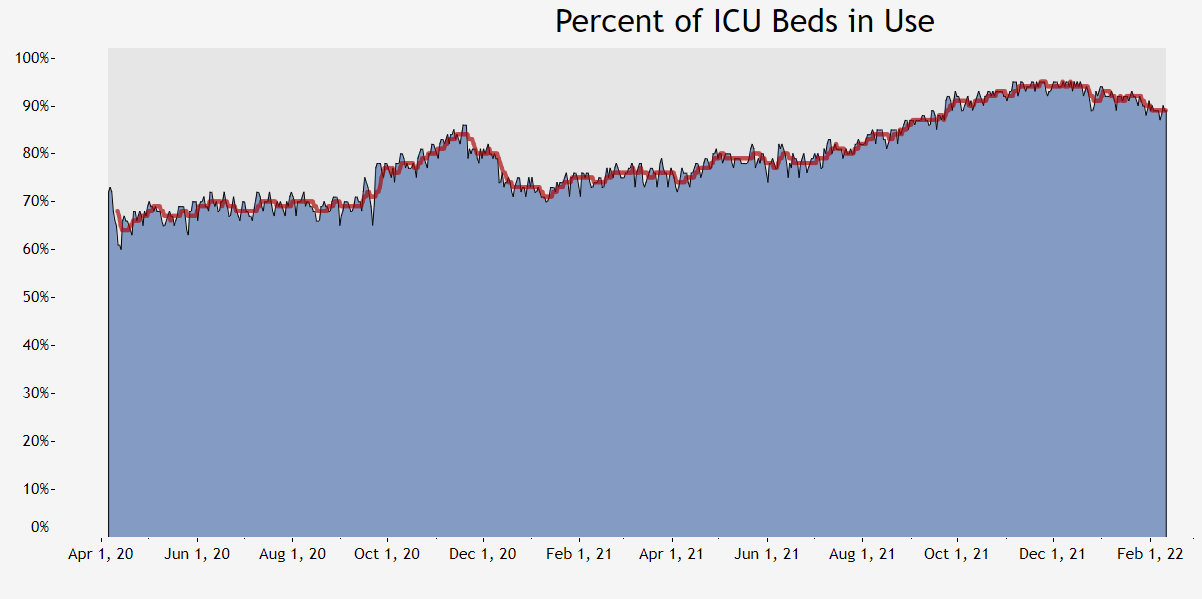

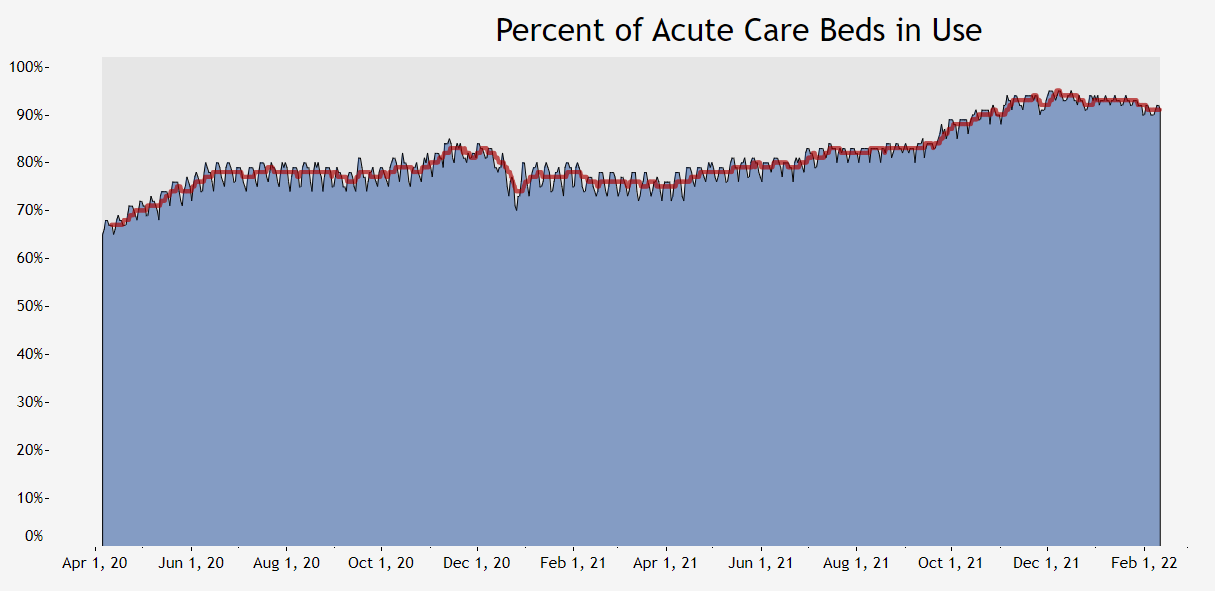

According to state data, patients hospitalized with COVID have reached the lowest levels since October, and yet ICU bed capacity sits at 89% statewide, with acute care bed capacity at 91%.

“What you’re seeing at the state level is what we’re experiencing at the hospital level here at Denver Health,” Dr. Anuj Mehta said.

At Denver Health, Mehta said they aren’t bringing as many COVID patients into the ICU, but their levels remain extremely high for a number of factors.

“We’re routinely operating above 90%, which is really busy,” Mehta said. “What we’re seeing is the non-COVID patients continue to be really sick, sicker than they were even six months ago. I think that’s a function of people, even without COVID, having not gotten the best routine primary care, so they’re coming in much sicker and staying in the hospital for a lot longer.”

Across the state, ICU capacity has been above 90% since late September. It’s just now fluctuating under that number in February.

Julie Lonborg with the Colorado Hospital Association said across the state, hospitals are dealing with similar issues to Denver Health: Coloradans are showing up to the hospital sicker than before. While delayed care is a part of that equation, Mehta said the issue can be exacerbated by mental health, substance use and the cost of care for things like medication.

“As they’re sicker they need more intensive and sometimes more invasive treatment,” Longborg said.

Lonborg said the combination of delayed care and even self-treatment fuel the increase in acuity across the state, which is how the medical community measures the level of sickness of every patient. On top of that, Mehta said they’ve seen some patients who are out of work over the course of the pandemic and can no longer afford medication.

Mehta said that this delayed care will have a ripple effect on the industry and it will take time to recover.

“We’ve delayed colonoscopies for example throughout the health care system, preventative screening colonoscopies or preventative screening mammograms and now we’re diagnosing later stage cancer,” Mehta said. “And we’re gonna see the consequences of that over the next several years.”

Mehta said they’ve seen an increase in people hospitalized for substance and alcohol abuse as well.

“This problem is not something that’s limited to just the next month or three months until we ‘get back to normal.’ This is an ongoing healthcare issue both in terms of the capacity of what we as a health care system can provide, but also in terms of how sick the patients are that will continue to be a problem for I think the next several years,” Mehta said.

The other issue contributing to the bed capacity crunch is staffing.

The CHA has seen national estimates that as many as one in five workers in health care has left the industry over the course of the pandemic. This is mainly attributed to burnout or early retirement. Couple that with a structural issue, as Mehta describes, in the health care system: traveling nurses. Nurses can make a lot more money to travel to spots that need more help. As a result, there are fewer nurses willing to stay put in one spot for lower pay.

While people may point to vaccine mandates as an explanation for why staffing levels are so low, state data indicates less than 2% of Colorado’s health care workforce was let go due to vaccine mandates, and nearly 5% of the workforce was granted a religious or medical exemption.

The staffing shortage across Colorado and the country has had a ripple effect, meaning hospitals like Denver Health are struggling to send patients to other acute care settings, like skilled nursing facilities, home health care and long-term care.

The looming issue both Mehta and Lonborg see is the healthcare workforce not being able to sustain high levels of capacity for such a long period of time.

“When you’re in the middle of the trauma, the middle of the battle, adrenaline will carry you for a long, long time,” Lonborg said. “As pandemic winds to endemic and they take a deep breath for the first time in two years, they’re exhausted, they’re gonna need a break. That’s concerning to us.”

“The health care workforce that continues to show up every day is resilient,” Mehta said. “We show up because we care, and we want to do what we can to save as many people as possible.”

Mehta said the best thing Coloradans can do to help the situation in our hospitals is to look after their own health.

“What we need to be able to do is get people back to seeing their primary care doctors,” Mehta said. “We need to work to get them the right medications.”