WASHINGTON — Conversations that take place at The Wall, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the Mall here, are reminders of how intense the memories, emotions and experiences are that this polished black granite wall stands to soothe and heal. They’re also reminders of a new chapter in the memorial’s life that its founder hopes will help it to further enrich the country and its veterans.

“Combat wounded,” is how O’Donnald Parker describes himself. The Washington, D.C. native served in Vietnam from January to December 1970, during which time he earned his Purple Heart. “Finger shot off,” he said, as he used his right pointer finger to point to the stub where his left pointer had been before a firefight north of Saigon 45 years ago. “Shot in the back of my hand here,” he said, while standing next to The Wall.

He also described why he visits the memorial multiple times a week, and looks at the names of his fallen comrades.

“When I reach out and touch their names on The Wall, I become a part of that memorial. I become a part of them again,” he said. “This is a healing place. It’s a place where I come to heal.”

And as the presence of North Carolina high school student Caitlin Claus and her family at The Wall on a recent afternoon showed, it draws people born long after the war ended, as well as veterans and others. “It’s very raw emotion,” Claus said, after making a rubbing from The Wall of the name of her grandmother’s cousin, Michael Rowcroft, from Roosevelt, Long Island.

More than 100 million people have visited the memorial since it was dedicated in 1982. “So it is a part of the American fabric,” said Jan Scruggs, who has every reason and right to make that statement.

Scruggs, a two-tour wounded Vietnam combat veteran, came up with the idea of a memorial in the late 1970’s. He then created the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Foundation, and through it oversaw the memorial’s design, construction and dedication.

“It’s absolutely an amazing thing,” Scruggs said in an interview, “after the dedication in 1982, to see hundreds and hundreds of items that were left there. And this behavior continued year after year after year.”

That practice continued and grew over the years, and what park rangers and volunteers at The Wall chose to do with mementos left there is at the heart of a pioneering new way visitors can now interact with the memorial.

For almost 30 of The Wall’s 33 years of existence, an unassuming storage facility as big as a city block has played a role almost as important to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Foundation as the memorial itself.

As much as one might want to, the 1 million cubic-foot building simply can’t

be called a warehouse. It’s a climate-, dust- and humidity-controlled facility run by the National Park Service, called the Museum Resource Center, or MRC. It houses about five million museum pieces and other items from Park Service-managed locations across the Washington, D.C. metro area, including the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Mementos left at The Wall had been stored at a small maintenance building for the first few years of the memorial’s existence, but in the mid-1980’s, they were moved to the MRC, which has since added some 400,000 items. They’re stored in row after row of large blue, plastic boxes, whose contents make up the MRC’s largest, fastest-growing and most unique collection.

“If it doesn’t fit into our blue boxes,” said Janet Donelin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial technician, during a recent tour of the building, “it goes into our oversize shelving.”

A look on those shelves showed a large collection of dozens of oversized plaques, a table-sized model of a military boat, a three-by-three-by-three foot bamboo cage, and hundreds of other large objects left in memoriam.

One item though, was too big even for the oversize shelves.

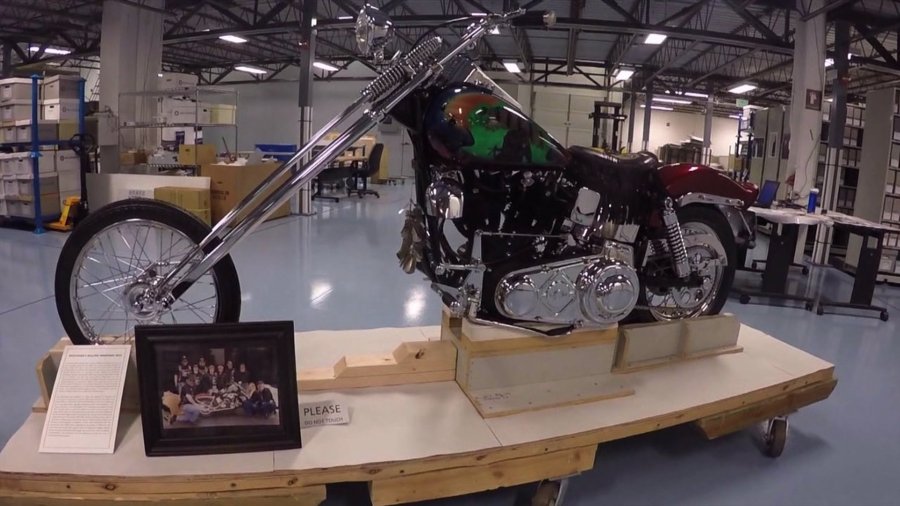

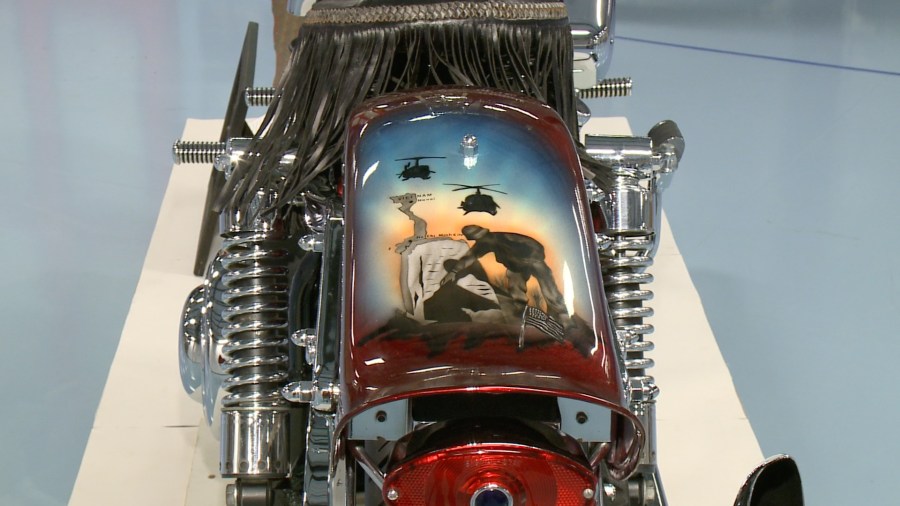

“One of the most remarkable artifacts that has been left at the memorial is this motorcycle,” said Bob Sonderman, the MRC director, as he pointed to what he called a “Harley-like” motorcycle in pristine condition, during a tour of the facility he runs.

“The bike,” he said, “was created to honor their fallen brethren, and POWs and MIAs,” by a group of Vietnam veterans from Wisconsin, who are also major motorcycle enthusiasts who ride to the memorial in Washington every year in Operation Rolling Thunder.

“The collar of the throat” of the bike, said Sonderman, as he pointed to a pipe at the front of the mechanical workings of the vehicle, is covered with “a series of reproduction dog tags of those missing in action” from Wisconsin.

But it’s in the thousands of blue plastic boxes, and on their neighboring blue storage shelves that house the oversized items, are far more of the most remarkable, but tragic stories of war’s effect on people.

Donelin, the technician who oversees the collection and storage of mementos at the memorial, showed a handmade pine box, about four feet long and eight inches high and wide, decorated with photographs and inscriptions. Inside the box was a section of a helicopter’s rotor blade.

It was from the chopper in which SSGT Terry Elliot and his crew crashed in Vietnam. Members of a POW-MIA joint task force search team found the rotor blade section during a post-war trip to Vietnam, in search of missing service member’s remains and mementos. They’d found that the rotor blade was being used at the time by a local farmer as a fence post.

SSGT Elliott’s remains, however, have yet to be found, so he is officially still listed as Missing In Action. Because of that, his sister built the coffin-like display case for the blade of the helicopter in which her brother was last seen alive, as a form of closure without remains.

Another item of note is “a returned, unopened care package,” as described by Memorial Fund senior curator Jason Bain during the rarely done tour of the MRC’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial collection.

Perishable items are generally not preserved in the collection, but an exception was made for the care package. It was sealed in plastic by the brother of Army Private First Class, or PFC, Charles Stewart, Jr.

The package had been sent to PFC Stewart by his parents. “It was returned, sealed and unopened,” said Bain, as he held it up with damage preventing latex gloves, “with this label in the lower right hand corner reading ‘KIA 10/31/72.'”

KIA is an abbreviation for killed in action.

“One can imagine how his parents must have felt to have received the care package with this KIA stamp,” Bain said, “and to have this physical reminder of the notification of his passing.”

“His brother made a point of bringing it” to The Wall, Bain added, pointing to an attached note addressed to PFC Stewart from his brother, “and essentially telling him in the note, ‘Mom and Dad wanted you to have these cookies and Kool Aid, it’s time that I bring these to you.'”

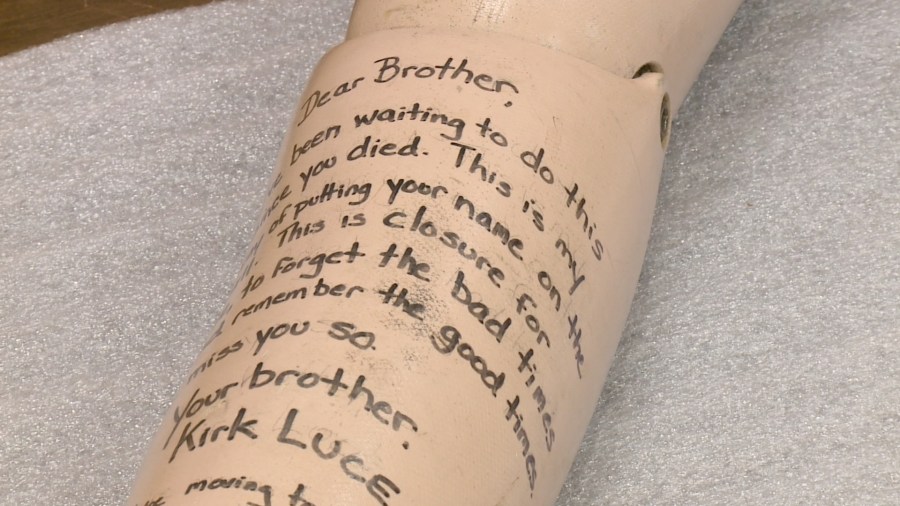

Bain, the curator, went from that item that left it to the imagination as to what the parents of the fallen soldier had felt, to a memento that came from a parent herself. It featured a handwritten letter that “is one of the most moving from the entire Vietnam Veterans Memorial collection,” Bain said.

He then read the letter from the mother of PFC Donald Detmer, left at The Wall with a handmade item, in October,1990. “‘My dearest son,'” the letter read, “‘today I am coming to see your name on The Wall. I haven’t been ready until now, but I knew that I must see it before I die. I miss you so much. I think of you every day. You had so much of life to live, and your life was taken so quickly. With lump in throat and teary eyes, I am on my way. I wanted to bring your teddy bear, but I just couldn’t part with it. Instead, I brought your first sweater. You’re always in my heart. How I love you. God be with you til we meet again. Love, Mom.'”

The raw emotion of that letter underscores a key aspect to the memorial that Jan Scruggs, its founder, described. “This is something that really is interactive,” he said. “Not by standing back and looking at it, but by making physical contact with it.”

Not everybody is able to do that, however, or even to visit the traveling Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall display that the memorial foundation often tours around the country.

In part for that reason, but in large part because the items left at The Wall are so important to interact with, Scruggs said, “Thankfully we’lll now be showing them on our website, and over the years, we’ll be showing thousands of these.”

Copyright issues typically restrict most institutions from putting their collections online. But because the public was the source of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial collection, items from it are now being shown online, accessible by anyone from anywhere in the world.

One photo from the collection demonstrates why the online display of items is so important. It’s of “an unidentified location, an unidentified subject,” said Bain, as he showed the black and white photograph of a soldier standing alone on the street in a Vietnamese city or town.

“And our only real clue [about it],” Bain said, “is when we look at the back, there’s an inscription that reads, ‘Delta 71, your face haunts me and the name is gone.’ What we’re trying to do is connect the faces and the names.”

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website invites the public to do that.

The memorial and its online presence also go beyond Vietnam, as a pair of combat boots left at The Wall with an attached letter show. It was written by an unknown Iraq War veteran.

“If your generation of Marines had not come home to jeers, insults and protests,” the letter reads in part, “my generation would not come home to thanks, handshakes and hugs.”

Interacting with such items online is the next phase of the memorial’s mission, but that phase is a piece of an even larger plan to enhance the Vietnam Veterans Memorial experience for posterity.

“The next stage of this is to bring these thousands of items to the education center,” said Scruggs, referring to an underground building across the street from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial that’s slated to be built before the end of the decade.

When the education center is completed, thousands of the items left at The Wall will be available for viewing in person by the public. However, even though the process to get the building approved and sited is now complete, after a decade of work, something else vital is needed for the project to be completed: money.

The foundation reports that it’s raised about $30 million toward the education center’s construction, but in order for it and its collections and exhibits to be fully functional beyond the Vietnam War generation, about $120 million is needed.

The foundation, having started out as just a good idea whose time was long overdue, has proven its strength in raising funds for an important cause. It’s now calling on the same public that has contributed 400,00 artifacts to its collection, and visited the memorial in person 100 million times to contribute, if possible, to help it accomplish its latest mission.

TribuneMedia and All 42 of its local television stations have made a commitment to covering Vietnam veterans issues in order to give a greater voice to our family members, neighbors and friends who served, and to honor their sacrifices and contributions.