DENVER — As one of the few major outposts in the American West, Colorado isn’t short on oral history. And when Halloween comes around, the Centennial State is spoiled for choice when it comes to good ghost stories.

This week, FOX31 Denver is exploring some of our favorites — mostly those that are rooted in at least as much fact as folklore.

WEDNESDAY’S TALES: State’s 1st serial killers, Hitler’s ranch and a ‘vampire’

In Thursday’s edition, we explore Colorado’s high country, once a lawless land of miners and home to some of the state’s tallest tales.

So fire up those jack-o-laterns, grab your favorite variation on the pumpkin spice beverage theme, make sure the lights are on and read up on our state’s spookiest tales!

‘Silverheels’ name endures, if not her ghost

Mount Silverheels is a 13,829-foot peak in the Pike National Forest. You can wet your whistle or grab a bite at Silverheels Bar & Grill in Frisco. Youngsters attend Silverheels Middle School in Fairplay and some of their parents live on Silverheels Place.

What’s the source of the nomenclature? More like who.

She has been called Josie Dillon, Gerta Bechtel and Gerda Silber and been identified with the surname Keller in some adaptations of the tale, but her true identity remains a mystery. History knows her simply as Silverheels, a nickname given to a dance hall girl-turned-nurse in Buckskin Joe, an old mining town named for Joseph Higginbottom, who discovered gold in the area between present day Fairplay and Alma in 1959.

Why Silverheels? According to “Ghost Towns of the Rockies” author Robert L. Brown, the nickname was derived from the fair maiden’s “preference for silver-heeled slippers, which she wore when she plied her trade as an entertainer.” And legend has it that Silverheel’s beauty was only matched by her benevolence.

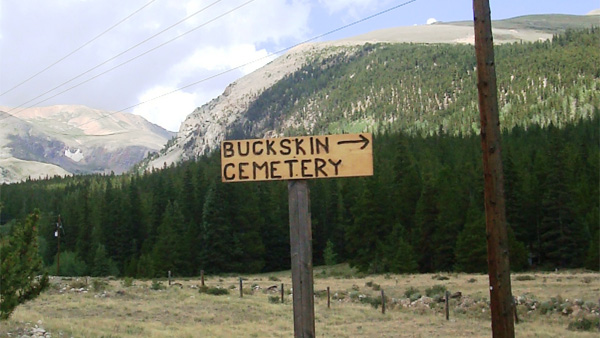

That kind spirit was allegedly put on display during a smallpox outbreak in Buckskin Joe in 1861, the evidence of which is clearly visible on the headstones in Buckskin Cemetery near Alma. Reports are that residents of Buckskin Joe, not unlike many other boom mining towns at the time, telegraphed a desperate plea for aid to Denver that fell on deaf ears.

While many fled, Silverheels stayed, going from cabin to cabin, caring for the sick miners and their families and burying the dead, inevitably contracting the disease herself.

The town batten its hatches and eventually came out of the epidemic in the spring of 1862. Grateful for her aid, the remaining miners took up a collection to thank Silverheels that reportedly totaled $4,000, a “small fortune” at that time according to “Strange But True, Colorado” author John Hafnor. But Silverheels was never found.

Legend has it, according to “Mysteries & Miracles of Colorado” author Jack Kutz, that if you go to the oldest part of the Buckskin Cemetery “where the wrought iron and wooden grave enclosures stand” you’ll see the ghost of Silverheels — her face veiled to hide the pockmarks that sullied her beauty — still tending to the graves of the victims lost in the smallpox epidemic.

Vigilante justice in Georgetown

The tale of Robert Schamle is also as sensational as the legend of his ghost.

That story appears in the book “Hands Up: Or, Twenty Years of Detective Life in the Mountains and on the Plains.” First published in 1882, the book is a collection of interviews with David J. Cook, the founder of the Rocky Mountain Detective Association, a secret organization that battled crime in the mostly-lawless high country.

Cooks described Schamle and his swift end in a fittingly sufficient fashion, calling Schamle a “brute of a tramp who murdered an inoffensive man in Georgetown a few weeks previous to his lynching in 1877.”

However, Schamle’s lynching couldn’t exactly be described as lawful. As Cook describes it, when he was eventually found and taken into custody in Las Animas, Schamle admitted to murdering his boss, the Georgetown butcher Henry Thedie, in cold blood for the $80 he was carrying.

After hearing reports that Schamle had also been accused of rape in Missouri, the townspeople of Georgetown, as Cook described them, harbored “no particular affection for Schamle, and must have suggested to him the propriety of making arrangements for a trip to a warmer climate than Colorado” — that being hell.

Cook said Schamle was imprisoned for all of one day in the Georgetown jail before a group of vigilantes busted him out and hanged him from the frame of a dilapidated building a few hundred feet away — a building that Cook said was “used as a pig pen.” Schamle’s body reportedly remained there for most of the day. Among the hundreds who laid eyes on it, Cook wrote, there was “not one pitying eye, or a single expression of sorrow or sympathy.”

According to “Ghost Stories of Colorado” author Dan Asfar, there have been “countless sightings of an emaciated young man reported around town, appearing one moment and gone the next.”

Tall tale in Colorado’s deepest cave

Unless you’re a world-class spelunker, there’s a good chance you have heard about the legend of La Caverna Del Oro — or know that it has gone by a bevy of different names throughout its haunted history, which began in the 1500s.

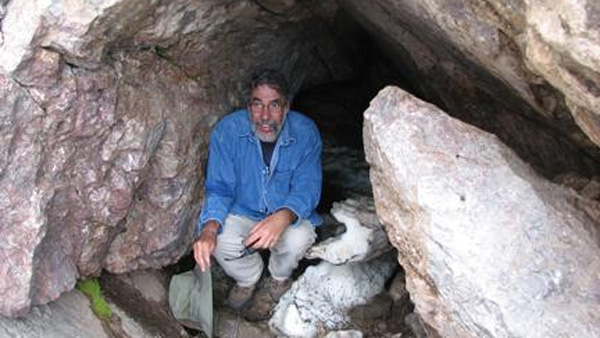

Located at just over 12,000 feet on the side of a ravine in Marble Mountain in the Sangre De Cristo mountain range near Westcliffe, Colorado’s most treacherous black hole looms. It has gone by many names, including La Caverna del Oro, Marble Cave and, most recently, the Spanish Cave.

According to “5280” magazine writer Peter Bronski, an unnamed local newspaper was the first to report in 1919 that an exploratory party entered the cave and found “a skeleton clad in Spanish armor lying chained in a pit inside the cave, an arrow piercing its rib cage.” Another version of that tale was reported in 1932, according to “Colorado’s Strangest: A legacy of bizarre events and eccentric people” author Kenneth Christian Jessen.

What has drawn explorers to the cave for hundreds of years? Legends of gold, of course. In addition to tales of the chained skeleton, legend had it that a set of oak doors bar passage down a narrow shaft that leads to the untold fortunes.

While the legends of gold may be far-fetched, the Spanish Cave does in fact exist. According to Bronski, an experienced spelunker who has explored the caverns himself, the Spanish Cave is the highest-altitude, large limestone cave in the U.S. And with a vertical relief of about 750 feet, it’s the deepest cave in Colorado.

Thought Bronski couldn’t find any human bones, he did come across plenty of bones of animals that met their untimely ends after falling deep into the cave.